Language as a Decontextualized Object

Ideologies are everywhere. They are the integrated patterns of ideas and beliefs that people and cultures hold, and language learning is full of them! Though you may not have realized it unless you have some background in descriptive linguistics. It’s important for learners and companies like us alike to be aware of what these language learning ideologies are and where they come into play because ultimately they will do two dangerous things:

affect how well you’re learning this new language, and…

determine whether the way you are learning it is marginalizing less socially powerful speakers of that language.

So today I’m going to start with what I consider to be the most important of these language ideologies, language as a decontextualized object, and to help me I’ve interviewed a fantastic University of New Mexico scholar on the subject, Emma Trentmen! Check out her bio here.

Language as a decontextualized object sees language as separate from people, it’s users and creators, and removes it from its social context. This can take on different looks. Let’s go through two of them, one in a traditional language classroom setting and one in Duolingo and Babbel.

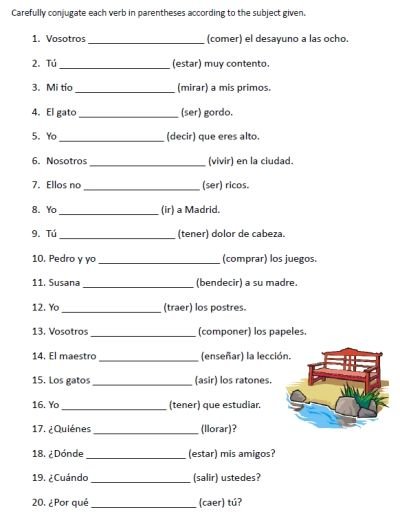

Traditional Classroom Setting: fill in the blanks

If you took middle school/high school Spanish you may have seen a worksheet like this one. It’s asking students to create change the verb in parenthesis according to the subject of the sentence, which are all conveniently placed before the blank line. In Spanish, speakers of all dialects employ a variation of subject-verb word order (subject before the verb or subject after the verb) or, more often than not, they will probably OMIT the subject. If you were learning a language through a realistic conversation, the subject would probably be known through context, but here they have stripped language of its social context. Different dialects of Spanish employ SV or VS or omitting the S in different social contexts: different speakers make different choices, and this worksheet preps you for only one possible scenario of thousands. And the one scenario they prepped you for is the one closest to English word order… little sus.

Pretend you are in the classroom right now, being asked to fill out this worksheet. The critic that I want to develop in you should be thinking the following: in what situation would I have to talk about y’all having breakfast at 8 (1), my uncle looking at my cousins (3), my cat being fat (4), and me wanting to go to Madrid (8)??? Answer: none. Yet again, language got stripped of its context.

One last thing, you’re working with vosotros twice and ustedes once (both used for 2nd person plural: y’all), despite vosotros really only being used in parts of Spain, while ustedes is used by the vast majority of Spanish speakers.

This is why by learning this way, you are not prepared to adapt to how speakers are actually speaking in the majority of the Spanish speaking world nor to any specific socio-cultural conversational scenario that could prove useful to you if you actually wanted to speak Spanish outside of the classroom, and you’ve just upheld the prestige of northern Spain over latin american speakers.

are we getting the picture now? Let’s see add on what this looks like in Duolingo and Babbel.

Duolingo and Babbel: “15 minutes a day”

Both of these apps attempt to get you on their platforms by convincing you that if you just spend 15 minutes a day with us, you will eventually get to speaking that new language! This does two unfortunate things.

First, it gives you a false idea that you could actually get to communicative fluency by spending a tiny amount of time each day repeating phrases or translating sentences while you eat breakfast as if this was some sort of workout exercise to get fit.

and second, there is this minimizing phenomenon that comes with seeing language as something that you can quickly “consume” or “workout” a little each day, which can only be “done” if you’ve removed it from it’s infinite number of contexts. Babbel apparently describes this as learning the “basics”. Babbel and Duolingo are framing language learning as the acquisition of an object that you can feasibly break down into its component parts, like a smoothie, but by doing so they have minimized the extraordinary effort that it is to use language as a speaker. Even for you right now reading this, to have gotten to this point in English (whether it was your first or third or fifth language) takes a tremendous amount of input from a variety of different speakers in a variety of different social contexts and years of trial and error on your part.

To ignore that effort supports a monolingual view of the world, where because you and most people around you only speak one language, you see multilingualism as something distant and foreign so you get the (incorrect) idea that you can learn it in just 15 minutes a day! ha.

Emma Trentmen points out and breaks down more examples of Duolingo enacting the language as a decontextualized object ideology in this amazing blog post.

So why can’t we take language out of its social context? Because that’s exactly what language is: an inherently social act. It cannot be stripped from people because people make and shape language according to what meaning needs to be conveyed at a certain time in a given social setting, who they are talking to, who they are talking with, what feelings they have in their mind at the time of talking, the physical space in which people are talking in, their gender, social class, not to mention the whole host of unquantifiable learned cultural and linguistic practices that a given person carries with them up until the moment of speaking. Language is context.

Now let’s take a look at just a few of the things that Faena is doing to make sure that we don’t fall into the dangerous ideology.

Faena: context is king

Learning method:

with Faena we are organizing our learning through realistic social situations. For example, in the beginning of the game, you are dropped off into this Andean community and you don’t know anyone in town except for one character. In order to get to know people, this one character teaches you how to run through a greeting with them (depending on who they are;) and how to introduce yourself. How you interact with each character in the game will depend on the task at hand, who they are in the community, and a few other things that we can’t reveal right now!

Character representation

Faena will have characters voiced by real native-speakers that are MULTILINGUAL. Meaning that while you’re walking through the town market, you will overhear a bunch of languages, not just Spanish, and these will be accurate representations of what multilingualism and code-switching look like in Colombia (since the game takes place there). We also will have most of these characters have dialects from all over Colombia, but we will have various characters that will be from other areas in Latin-America in the hope that the player can get exposed to as many different dialects and ways of speaking

Years of learning:

We understand deeply that one never stops learning another language, so there is no explicit end goal here. But we do want to market Faena as your biggest dependable language learning solution in the years that it’s going to take for you to get to a point where you’re confident conversing with other speakers in various social contexts. So none of these 15 minutes a day myths, we want to captivate you for hours on end, and once you finish the game, we want you to be excited for the next installment so you can binge again! (not unlike what I did with Stranger Things).

So what I want you guys to take away from this first blog post on language ideologies in language learning is just to have a critical eye on what’s being offered to you and to understand that it can be better, and it will be once we release Faena! Stay hungry!